Your guide to N.C. oysters, from the salty sea to the half-shell

by Allison Ballard on October 15, 2022 | Reprinted from Wilmington StarNews

As fans of local oysters already know, they are a delicacy that can be enjoyed year-round. That being said, it’s a big time for the bivalves. We’re in the middle of N.C. Oyster Week, and the official oyster season (which dictates the harvesting of wild oysters) begins Oct. 15 and ends in March.

Look around and you can find oyster events, oyster specials and even oyster collaborations, like an upcoming oyster beer from Wilmington’s Mad Mole Brewing. Oysters are big in the state and poised to become even bigger. With that in mind, here’s a look some of the basics about N.C. oysters.

The Napa Valley of bivalves

In his book “The Essential Oyster: A Salty Appreciation of Taste and Temptation,” author Rowan Jacobsen was the first to tout the relatively untapped potential of the Southeast, even saying that there was something of a renaissance in the industry happening from Virginia to Florida. Since then, those in the industry decided to build on that idea that North Carolina could be a premier spot for oyster growing and harvesting.

Initiatives like N.C, Oyster Week (Oct. 10-16) and the Oyster Trail, which highlights businesses such as markets and restaurants that serve oysters and promote the industry, are supported politically and environmentally because oysters work on several fronts. It’s good business, meets a customer demand, and is a practice that can be done sustainably to clean and nourish the local waterways.

Previously: What is the N.C. Oyster Trail? And where are the Wilmington-area stops?

“It’s a win, win, win,” said Chris Matteo, Bayboro-based oyster farmer and president of the N.C. Shellfish Growers Association. “It’s something that actually leaves the estuary better off that when we started.”

Jane Harrison, a coastal economist with North Carolina Sea Grant, said oysters have an economic impact of $27 million for the state and provide more than 500 jobs. But goals are in place to reach $100 million and 1,000 jobs by 2030. Even while wild harvest production has been decreasing in recent years and was estimated at around 50,000 bushels last year, preliminary data from 2021 show that farmed oyster production has outpaced it for the first time. Production was around 59,000 bushels, a 111% increase over 2020.

“Even a few years ago, a lot of the oysters consumed in North Carolina were imported from other places, but that is changing now,” Matteo said.

Wild and farmed

When you’re talking about oysters on the East Coast, they’re really all the same. Species, that is. The indigenous oyster is called Crassostrea Virginica, and they are known to be briny and savory with minerality.

From there, though, there can be a lot of differences. Farmed oysters often have a different chromosome make up that makes them suitable for year-round harvest. Other differences can be a result of the salinity of the water, what algae and plankton the oysters eat, and the movement of the tide. This merroir, a sea-inspired version wine’s terroir, can help explain why Stump Sound oysters are different from those growing in nearby Topsail waters, for example.

“They can have a very diverse flavor profile,” Matteo said. “Those grown closer to the Atlantic Ocean have a higher salinity and minerality. Further inland, in waters with a mid-salinity, you see oysters that can be sweet and buttery.”

While oyster aquaculture takes place all year long, commercial fisherman must wait until the oyster season begins. Limits and site restriction are in place. But pros like Ana Shellem, of Shell’em Seafood Co., will forage and fill orders for her restaurant clients. She worked in the hospitality industry before she switched careers. Other fishermen sell to markets and distributors, or direct to customers. Breece Gahl accepts bushel pre-orders from his Wrightsville Beach-based Fresh2U Seafood business, for example.

Because of a difference in the way they develop and grow, the wild oysters are more likely those found in clusters and are the safest to eat raw when collected in the fall and winter months.

All year round

That’s not the case for all local oysters, though. These farmers say they are continually trying to get the message to consumers that mariculture oysters are safe to eat, even in months that don’t end in ‘R.’

“Always. I’m always telling people,” said Matt Schwab of Hold Fast Oyster Co. He’s been in the business about seven years with a farm in New River.

At the time, there were only a handful of oyster famers working in the state. Now, there are more than 75 and the water acreage being farms has increased for a total of more than 2,100 acres in 2021, Harrison said. The new people entering the business sometimes take it on as a second (or third) career or are starting an oyster farm right after completing an aquiculture program at college, Matteo said.

Holden Davanzo was a stay-at-home mother and manager at an ice rink before she bought her cousin’s oyster business, Anchored Life Oyster Farm, three years ago.

“It was definitely a learning curve,” she said. But now, she goes out on the boat every day to tend her oysters in Stump Sound and New River.

“But I love it. I have a new appreciation for the ocean,” she said. “And it’s beautiful. I see dolphins. Sometimes I’m out there and I think ‘This is my office.'”

The business is really taking off this year, for her Top-Sea-Turvies and New’d Pirates. Although the oysters are the same species, many farmers name their selections for branding and to let customers know what they’re getting.

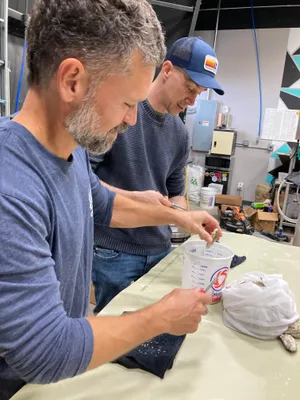

Schwab, for example, grows a variety he calls Seabirdies especially for Seabird restaurant and chef Dean Neff in downtown Wilmington. The chef and the farmer partnered with Mad Mole Brewing this Oyster Week to make a Seabirdie Oyster Gose, brewed with oysters (shells and meats), bitter orange and spiceberry.

Others new to oystering are James and Sarah Rushing Doss, of the newly renamed Rx Chicken & Oyster restaurant in Wilmington. They’re growing their own oysters, named after their dogs, with the help of James Hargrove and Middle Sound Mariculture, for when the restaurant reopens later this year. By the way, the couple also have their commercial fishing and dealer’s licenses, so they can serve fish they catch and spear themselves, including the invasive lionfish.

The business isn’t an easy one, Harrison said. Oyster growers and harvesters have to deal with hurricanes and subsequent closures due to water quality concerns, as well as loss of product. She also said that it cost as estimated $20,000 per acre to start an oyster farm. But it’s encouraging to see a new generation of people entering the business.

“There’s definitely a demand,” Harrison said. “People want local seafood.”

Allison Ballard is the food and dining reporter at the StarNews. You can reach her at aballard@gannett.com.