One Oyster At A Time

by Sam Jones on October 18, 2023 | Reprinted from NC State CALS Magazine

From the salty breeze of the Outer Banks to the winding undulations of the Blue Ridge Mountains, a new food trail is introducing people to a rather misunderstood creature: the eastern oyster.

In the spring of 2020, North Carolina Jane Harrison, a coastal economist on the North Carolina Sea Grant extension team, launched the NC Oyster Trail, a grassroots network of oyster growers and fishers; seafood markets, restaurants and festivals; environmental education centers; and conservation organizations. The trail has grown to encompass 80 sites offering memorable experiences for foodies and farm fanatics of all kinds.

Harrison wears a few hats—she is an affiliate faculty member in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics and a graduate faculty member in the College of Natural Resources. Her primary position is as coastal economics extension specialist for NC Sea Grant, where she repeatedly heard from shellfish growers about the need for more consumer awareness of their tasty bivalves.

“Some of my agribusiness students have tried their hand at growing oysters,” Harrison says. “Oyster farmers have stepped up to the plate to grow shellfish with innovative marine aquaculture technologies, providing a truly sustainable protein.”

“The NC Oyster Trail is about changing our culture, one oyster at a time.”

Despite their environmental benefits, Harrison says oysters are not the No.1 seafood that people choose. Shrimp and salmon are still the most popular choices.

For those unfamiliar with oysters, or maybe even wary of them, consider these salty jewels an adventure for your taste buds. Oysters possess their own distinct flavors, known as “merroir,” derived from the unique aquatic environments in which they are grown. Some oysters might have a savory umami taste while others have a mineral flavor. They can be rich or light, and their saltiness varies widely.

Oysters and Food Safety

Bacterial pathogens can live in raw oysters, but many precautions are taken before reaching the consumer’s plate.

“The Division of Marine Fisheries does not allow the harvesting of oysters from water bodies that have poor water quality. If there is a rain event, which creates some pollution from runoff from the nearby land, they will automatically close shellfish beds in that area. They will then test the waters before they’re allowed to be harvested again.”

-Jane Harrison

Despite these qualities, Harrison has found that many people are still unsure about when to eat oysters, how to prepare them, and whether or not they’re safe to eat. She sees the NC Oyster Trail as a critical educational tool for consumers and policymakers.

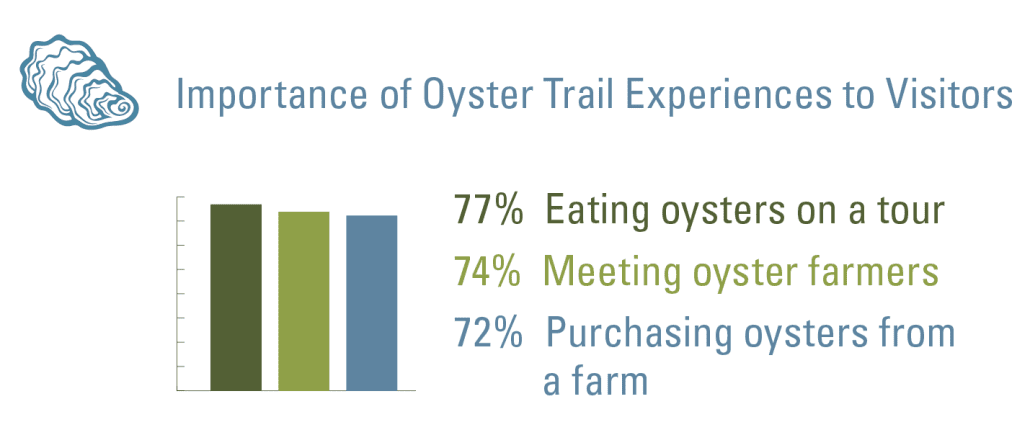

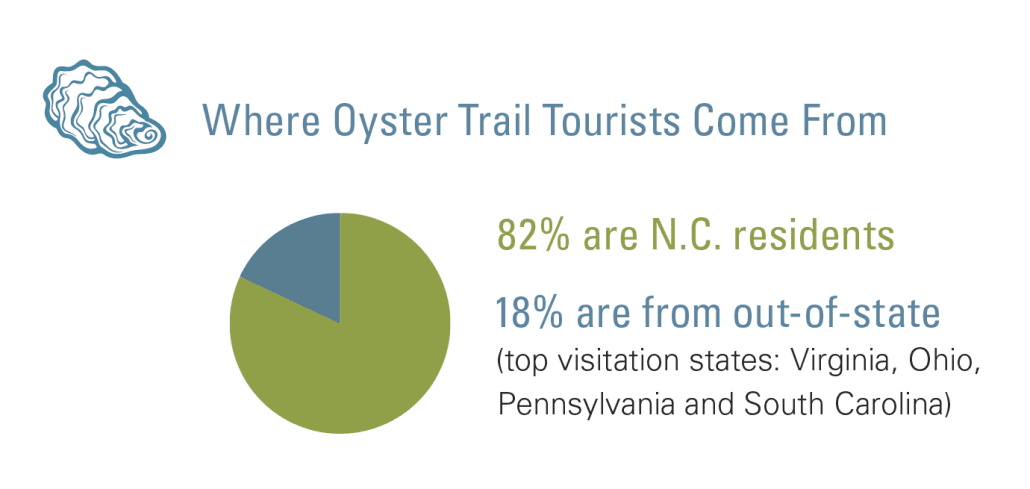

To ensure the NC Oyster Trail would be successful, Harrison conducted a market demand study led by Whitney Knollenberg, an associate professor in the Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism. Feedback from over 1,000 coastal visitors and local seafood consumers helped determine the level of potential interest in an oyster trail. Harrison and her colleagues used the results to map out a trail with a variety of family-friendly opportunities to help ease oyster skeptics into the wonderful world of life on the half shell.

“Our study showed a high demand for seafood educational experiences, especially for shellfish farm tours,” Harrison says.

According to their study, the average willingness to pay for an oyster farm tour was $150 per person. Whether booking a private boat tour in Topsail Sound or ordering a dozen fried oysters for happy hour in Raleigh, visitors to the NC Oyster Trail are part of the seafood industry’s $300 million annual contribution to the state’s economy. That significant economic impact comes with positive environmental impacts as well.

“People really do want to understand how oysters are grown and their role in the coastal ecosystem,” Harrison says.

Myth Busting: Only Eat Oysters in “R” Months

Before refrigeration, harvesting oysters in hot summer months (those without “R”s) from May to August made it difficult to bring the oysters down to 50 degrees quickly enough to prevent bacterial pathogens. With the advent of ice and refrigeration, that’s no longer true for farmed oysters.

BUT … wild oysters are off-limits for harvesting in non-”R” months because they spawn in the summer.

Wild oysters provide many ecosystem services as a keystone species. An individual oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water per day, which greatly improves water quality. They also supply food for other marine organisms and provide spawning habitat for juvenile fish and crustaceans. However, their numbers have been decimated over the years due to overharvesting and environmental degradation.

The NC Oyster Trail works to counterbalance this pressure on wild oysters by promoting the consumption of farmed oysters. Some sites on the trail showcase living shorelines made from recycled oyster shells that create new wild oyster habitat and protect coastal land from hurricanes. The NC Oyster Trail offers boat and kayak tours of conservation projects as well as volunteer opportunities to help restore damaged environments.

“The NC Oyster Trail is about changing our culture, one oyster at a time,” says Cody Faison, co-owner of Ghost Fleet Oyster Co., which offers customized oyster farm tours in Hampstead.

Three years into running the NC Oyster Trail, Harrison’s ongoing surveys have found that nearly 90% of visitors are satisfied with their experience. Another sign of success: Farmed oysters now represent more than half of all the oysters consumed in North Carolina.

“We want those who depend on the coastal environment for their livelihood to be successful,” Harrison says. “Especially in our coastal communities, working on the water is a heritage. It’s a part of North Carolina’s history. Being able to sustain and evolve these practices is critical to maintaining our culture, for our sense of self and identity.”

For more information about the NC Oyster Trail, visit ncoystertrail.org.