Shell shock: North Carolina oyster farmers face pushback from critical beach property owners

by Emory Rakestraw on February 1, 2023 | Reprinted from Business NC

Looking out onto Bogue Sound, one might envision a permanent vacation, the expanse of water and marsh beckoning visitors to sit back, relax and soak in the uninterrupted views. Others see possibilities, namely an opportunity to jump into North Carolina’s $30 million oyster industry, one that’s expected to hit $100 million by 2030.

These two outlooks are creating a clash in coastal North Carolina. Potential oyster farmers are hoping to land water leases and set up small farms, while homeowners and local lawmakers are fighting back with moratoriums. Current discourse threatens to halt a burgeoning industry flush with environmental benefits.

In Onslow County, the estuarine waters of Stump Sound envelop Permuda Island, approximately 1.5 miles long, with archaeological evidence dating the earliest occupation to

300 B.C. Native Americans would scour the island for oysters, clams, scallops and crabs. Centuries later, when Europeans made landfall on the North Carolina coast, towering oyster reefs beckoned a new economy as bushels were traded for supplies.

By the 1800s, North Carolinians would often tong oysters from the shallow-water mud, and as reefs and beds became depleted in Maryland and Virginia, “oyster pirates” armed with Winchester rifles traveled south. Using dredges that gathered both seed and mature oysters, they pillaged the waters of Hyde, Dare and Carteret counties until 1891, ceasing only when the National Guard interfered. By 1902 oyster harvesting reached its peak, with 5.6 million pounds of oyster meat harvested that year. There was essentially no regulation at the time, says Erin Fleckenstein, a scientist with the nonprofit N.C. Coastal Federation.

“The thing with oysters is that you’re not only harvesting the product, but you’re also harvesting the habitat,” she notes. “Centuries of harvest, disease, storms and water quality impacts from land development have decimated our wild population. It’s an uphill battle.”

The oyster is a simple creature, living life in one spot despite what Mother Nature or man might conjure. Oyster reefs modify and create habitats for other aquatic life, accumulate marine biotoxins, and help prevent algal blooms. The average adult oyster also filters up to 50 gallons of water per day.

Yet wild oyster populations have continued to struggle. Harvesting and disease decimated an estimated 95% of the natural oyster population over the past two centuries. Conservation efforts in recent years have helped raise the population to about 15% of its historic total, researchers say.

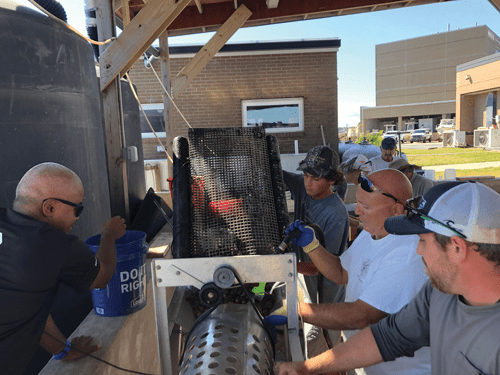

Oyster farming has stepped in to bridge the gap, providing the same environmental benefits and briny bivalves. Placed in their natural growing environment of sounds, marshes and intertidal waters, seed oysters (also called spats) reach harvest in racks, bags or cages. The spats are left in the water for about 18 months, tumbled by the tide, sorted for size, and often harvested at 2 or 3 inches.

These “manicured” oysters are shaped through the process of transferring and spacing, resulting in deep cups, hearty meat, and an aesthetic deserving of half-shell status. The majority are sold year-round, both locally and nationally, to restaurants, distributors or grocery stores. With nearly 2.1 million acres of estuarine waters in North Carolina, Fleckenstein notes the number of acres needed to have a sustainable aquaculture industry is only a drop in the bucket.

Farming oysters

In 2013, Chris Matteo shifted careers from finance and investment management to oyster farming, opening Chadwick Creek Oysters and Seed Nursery in Bayboro. At the time, Matteo was one of the few growers in the state, and Chadwick Creek’s nursery helped foster budding aquaculture businesses with Matteo advising hopeful farmers. In 2018, he became president of the North Carolina Shellfish Growers Association, which now has about 40 members.

Matteo compares the lure of oyster farming to that of purchasing a well-established vineyard. He says North Carolina has been called the Napa Valley of oysters because much like grapes, oysters take on the flavor of the environment they’re grown in. It’s called “merroir.”

Other farmers just enjoy living on the coast, participating in a labor of love. By 2019, interest in oyster farming gained prevalence in North Carolina, with 106 applications for leases.

“Obviously there are upfront costs, but once you have a barge or docking, the average oyster farmer is going to spend $25,000 to $50,000 per acre to set up, and these costs go down when you scale up,” says Matteo. Smaller farms generate profit margins of 40% to 50%, while larger ones can earn as much as 80%, he says. “For some people, the interest is in the money. For others, it’s aquaculture or conservation.”

After North Carolina’s shellfish aquaculture bill passed the legislature unanimously in 2019, Matteo expected oyster farming to continue gaining popularity. The bill established three 50-acre shellfish leases in Pamlico Sound and facilitated enterprise areas, or ideal locations, for small oyster farms.

Bogue Sound was poised to be the site of initial farms, but it quickly became a battleground after a shellfish grower received a lease approved by the state Division of Marine Fisheries. “Nearby homeowners in a condominium development did not like the idea of a shellfish farm within 1,200 feet of their property, mainly for view-shed reasons,” Matteo says. “That was the beginning of a coordinated effort to shut down all of Bogue Sound shellfish farming using a moratorium.”

Not in my backyard

With a maximum lease of 10 acres, one floating cage can fit as many as 150 oysters and spans from a single to six-bag system. Within 4 acres alone, more than 4 million oysters can be harvested. Buoyed by twin floats, cages are attached by lateral lines to a main line and come outfitted with removable caps that allow a farmer to fill the floats and sink the cage.

There’s nothing blocking water views beyond the farm. But Matteo cites a not-in-my-background, or NIMBY, mindset as the basis for North Carolina’s modern-day oyster war. Homeowners fear that their view might one day be compromised.

That opposition sparked a coordinated effort against shellfish farms that led to a moratorium in the same bill passed by lawmakers in 2019. “Now, no new leases for oyster farming can be permitted in Bogue Sound until the moratorium is lifted and any new growers cannot apply for a granted lease,” Matteo says. “At the time, there were only 16 acres in commercial production that triggered a shutdown of a 65-acre water body.”

In addition to opposition from beach property owners, adherence to the state’s Coastal Area Management Act is also challenging for the oyster industry. Prospective shellfish farmers must go through a complicated process to secure a permit approved by the N.C. Coastal Resources Commission. Matteo recalls a shellfish farmer giving up after waiting during a four-year, back-and-forth approval process.

“Although we are farmers, the Division of Coastal Management does not want to recognize shellfish farmers as such,” he says. “They do not want to say one way or another if we’re actually agriculture,” though industry officials consider it to be part of North Carolina’s $93 billion ag sector. He is working to gain support for the industry along with the N.C. Farm Bureau and other groups to prevent yearslong waits for applications and to block future moratoriums.

“Farm Bureau represents the farming community in this state, and we’re considered farmers. They’re very interested in things that affect shellfish growers and have been involved for many years,” he says. “For 2030, the estimate we’re hoping to achieve is a $100 million impact” when factoring the impact of shellfish dealers and restaurants.

Floating junkyards?

Since 2003, the North Carolina Coastal Federation’s Oyster Blueprint has served as a protection and action plan for oysters. It has restored nearly 450 acres of habitat, grown the shellfish aquaculture industry from $250,000 to $5 million, and built a coalition of nearly 25 partners. Alongside it is the Oyster Trail, a tourism marketing effort highlighting oyster farms, restaurants and conservation programs.

Still, the positive PR and water filtration benefits haven’t impressed some coastal politicians. Randall Bentley, a retired District Court judge and town commissioner in Indian Beach in Carteret County, called the farms “a floating junkyard” at a meeting last year. The few jobs created for oyster harvesting risks major job losses in the region’s tourism industry, he wrote in a letter to a local newspaper last year.

Oyster farming “could ruin permanently those sunset views on all the sounds of North Carolina,” Bentley wrote. “Then, we could try to ignore the loss of property tax dollars as people leave the sound waterways — resulting in falling real estate values for those hundreds of millions of dollars in residential homes and condominiums — on all the sounds of North Carolina.”

Atlantic Beach Mayor Trace Cooper has also criticized floating structures, calling them “industrial houseboats.” He’s a former member of the Coastal Resources Commission and a real estate developer. Other mayors, such as Sharon Harker of Beaufort and John Brodman of Pine Knoll Shores, have offered support for aquaculture. Meanwhile, development largely hinges on lease permits approved by local governments.

As of 2022, there were nearly 450 leases approved in North Carolina, totaling 2,221 acres. Research by UNC Wilmington and other institutions suggests that oyster farms lead to a higher density of adjacent wild oysters and aquatic animals, while reducing the cost of treating nitrogen for local communities by as much as $7,300 per leased acre annually.

“Wild oyster populations are severely depleted, and water quality is highly dependent on the oyster population,” Matteo says. “We’re providing ecosystem services for free that otherwise wouldn’t be occurring. Lastly, oysters are some of the most nutrient-dense forms of protein on the planet, and oyster farming is one of the greenest forms of protein production.”

Debates over new regulations and localities’ right to enforce leases are widely viewed as a hotter topic than in 2019. The Coastal Resources Commission recently asked N.C. Attorney General Josh Stein to consider issues involving the CAMA law. Fleckenstein says it’s about achieving the right balance.

“We recognize waters are a public trust resource and there needs to be balanced use of them,” she says. “It’s a big balancing act. Environmental and economic benefits speak volumes and help create a good framework and case for the expansion of oyster farms in the state.”