In Raleigh, a New Inland Fish House Anchors North Carolina’s Seafood Industry

The seafood industry is largely decentralized. But a new Locals Seafood market and processing facility in East Raleigh is helping get seafood to more North Carolinians.

by Andrea Richards on June 12, 2024 | Reprinted from Indy week

Lin Peterson, the cofounder of Locals Seafood, starts our tour of the company’s new East Raleigh market and processing facility by pointing out the fishing village Wanchese on a mural of North Carolina. It’s the state’s hub for the commercial fishing industry that sits, somewhat precariously, on the southern end of Roanoke Island.

The map isn’t detailed: it’s a large ocean-blue outline of the state that wraps around the corner of the building’s market space, unlabeled except for a small dot representing where we are now.

Still, Peterson is able to demonstrate the morning’s pickups and deliveries on it, tracing the trajectory of the four trucks active today (the company has eight total). One truck is in Wanchese waiting on fish that may or may not be coming in from fisherfolk who navigate the dangerous Oregon Inlet to get it from the Gulf Stream to the shore. Another truck is picking up mariculture-grown oysters, moving between the 12 family farms that Locals works with. A third truck is on its way toward Asheville, and a fourth is taking sheepshead from Raleigh to Olivero, a Wilmington restaurant.

Yes, taking Sheepshead back to the coast. As it turns out, thanks to the complications of geography and distribution, there’s no other way to get it there

While Peterson is mapping these trajectories, Ryan Speckman, the business’s other cofounder works his phone nearby, finding out what fish came in and from where, buying from his network of fish houses, and moving the trucks around accordingly. It’s all happening in real time.

“A normal seafood operation would just be Ryan on the market buying the fish people want—getting tuna 52 weeks of the year from somewhere in the world,” says Peterson. “The way we do it, Ryan’s more like a reporter of what’s happening on the coast, like a weather forecaster.”

This syncopated dance of boats, cell phone texts, and refrigerated trucks is what it takes to be one of the only seafood purveyors 100 percent focused on North Carolina product.

“It’s been our niche since we started,” Speckman says.

I don’t know if it was intentional, design-wise, but the way that the map wraps around the room in this new market visualizes the problem Peterson and Speckman sought to alleviate when they started Locals Seafood 14 years ago: the coast on one wall, the Piedmont region and western North Carolina on the other.

The work of Locals is in bringing the two back together. That’s what these complicated routes do, six days a week—reconnect the coast’s bountiful harvest to its inland inhabitants.

Ryan Speckman, the Locals Seafood co-owner, points out Wanchese on a map, a focal point in North Carolina’s commercial fishing industry, on Friday, June 7, 2024, in Raleigh.

For the uninitiated, prepare for a series of small shocks regarding the state of seafood: supply chain distribution is all over the map, quite literally. According to a recent New York Times article, 65 to 80 percent of seafood in the United States is imported, with exports netting around $5 billion a year.

The industry is likewise decentralized in North Carolina. Most of the seafood caught off the Tar Heel State’s coast is sent north, following already well-established distribution routes. That means the seafood you scarf down at the beach likely isn’t from there, and the best place to find North Carolina blue crab might be Maryland.

The realization that few folks in the state had access to North Carolina seafood is what inspired Speckman and Peterson to start Locals Seafood in 2010. The two met at NC State University studying fisheries and wildlife science. Over the past decade, they grew the business slowly, expanding from farmer’s markets to wholesale distribution services for grocery stores and restaurants. Along the way, they created seafood subscription services in Raleigh, Durham, and Asheville and opened two retail markets and restaurants—one in Raleigh’s Transfer Co. Food Hall (shuttered in 2022) and another in the Durham Food Hall.

Now, the new public-facing market in East Raleigh, which offers a stunning array of fresh and frozen seafood, as well as specialty items like dry-aged bluefin tuna belly and cured mullet roe, has a relatively small footprint in the renovated 10,000-square-foot building. Most of the building serves as the company’s whole-fish butchery and seafood processing house. There’s room for a potential restaurant too, but right now Peterson and Speckman are focused on processing and distribution.

The new facility triples Locals’ capacity to process North Carolina seafood and consolidates its operations close to I-40.

Location matters: Once you cut fish, the clock begins ticking. Processing near customers helps. An inland fish house like this market ensures that Locals can process and distribute seafood to more distant parts of the states, like Asheville, and still ensure the quality.

Biologists and wildlife conservationists emphasize the importance of connectivity—corridors that species can move safely through so they don’t get stuck in the sort of isolation that leads to extinction. Locals gives North Carolina seafood a safe passage from its home on the coast to inland parts of the state—even though that path may at times look convoluted, like taking sheepshead fish from the coast to Raleigh and then back again. Centralizing the operations in one place allows suppliers to connect to purveyors and customers across the state.

“We saw the writing on the wall years ago that to really do this correctly, we needed the proper facility,” Speckman says as we walk through the massive space. “And the proper facility is pretty much this.”

Michelene King pulls bonitos from the ice before processing them at the Locals Seafood market. Photo by Angelica Edwards.

If seafood had a relationship status, it would definitely be “it’s complicated.”

There are a number of nonprofit watchguard organizations that monitor sustainability nationally, and as far as the state’s supply goes, many regulations prevent overfishing.

“Our commercial fishermen are great environmentalists—they want to see the continuation of the species,” John Aydlett, a seafood marketing specialist with the NC Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, tells the INDY. In 2021, North Carolina’s wild-caught seafood industry contributed almost $300 million in value to the state’s economy and provided some 5,500 jobs. The state’s growing aquaculture industry brings in an annual revenue of $60 million.

As a consumer, it can be hard to keep up with what best practices are: Wild caught? Farmed? Fresh? Frozen?

“We always tell people that if you can’t find local seafood, the best rule of thumb is to buy domestic,” says Speckman, who has concerns about both the quality of overseas products and their social and environmental impacts.

Of course, thanks to this new market—and Locals Seafood’s presence at area farmers markets, in stores (Durham Co-Op and Weaver Street Market), and as suppliers to restaurants—it isn’t as hard as it once was to get local seafood.

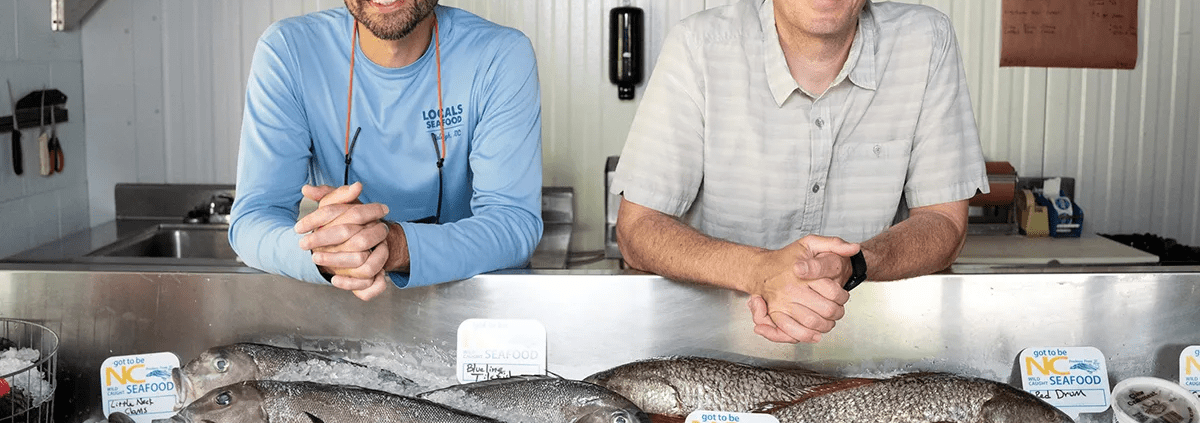

(From left) Locals Seafood co-owners Ryan Speckman and Lin Peterson pose for a portrait. Photo by Angelica Edwards.

Just ask Andrea Reusing. The award-winning chef/owner of Chapel Hill’s Lantern Restaurant loves to tell folks how, when she first moved to North Carolina in 1999 and worked at Vin in Raleigh, she’d drive her station wagon to Tom Robinson’s in Carrboro twice a week to get a haul of local seafood.

“There was no east-west distribution of North Carolina fish,” Reusing says. “When I got NC fish from a purveyor, it would have gone up to the Fulton Fish Market in New York City, and then maybe gone down to Atlanta or through Charlotte before coming back. Before Lin and Ryan started Locals there was no other way to get local seafood—except for driving to the coast or maybe getting some through FedEx.”

Right now Reusing features several items procured through Locals on the Lantern menu.

“We have three different kinds of oysters from three different family cultivators,” she says. “We have wild head-on shrimp and sheepshead, which is one of my favorite fish—it feeds on crustaceans, so it’s very rich and nutty.”

Not only has Locals helped solve a critical supply chain problem for inland restaurants and consumers, but it’s also helping to expand an appetite for seafood beyond the familiar standards of shrimp, salmon, and tuna. If you care about seafood sustainability, the best step is to eat a more diverse range of fish.

When asked about his relationship with Locals Seafood, Ricky Moore, the James Beard Award-winning chef of Saltbox Seafood Joint, responds by emailing over a photo from 2013.

Ricky Moore outside of the original Saltbox location in 2013. Photo courtesy of the subject.

It shows him in his trademark floppy fisherman’s hat outside the kitchen entrance at Saltbox’s original location, signing a receipt with a Locals delivery person. There’s a refrigerated box and cooler at Moore’s feet, and the men are framed by the two company’s vans parked side by side. For Moore, the photo speaks to the nature of a more than a decade-long partnership between a restaurant and a vital supplier.

“We’ve got history together,” he says, explaining that from the very beginning his concept for Saltbox—preparing the kind of local, seasonal seafood caught by North Carolina fisherfolk that Moore grew up eating in eastern North Carolina—necessitated a supplier with a similar vision. “Not too many people were doing it the way I needed it to be done to bring my restaurant concept to life.”

When Moore first opened Saltbox, he installed a “Trust Me” board alongside his regular menu of seasonal items to help introduce patrons to less familiar fish species.

“In the beginning when Lin and Ryan would bring me stuff like sheepshead, people would be like, ‘What is a sheepshead?’ Only folks who grew up eating stuff would know about it,” says Moore. He was happy to find a source that could supply an array of seasonal, local fish, and thus a symbiotic relationship between supplier and chef began: “I’d say, ‘Bring it to me, man, I’ll sell it.’”

“What’s being served in most places are things that people are culturally conditioned to eat. Everybody knows what salmon is, it’s been marketed to us as healthy. Omega-3s, yada yada,” Moore says. “I like to speak about whole fish: growing up in eastern North Carolina, we ate a whole lot of whole fish, smaller fish like croaker and spot. Unless you’re regionally connected to it as a part of your heritage, you would never see those fish on the menu. And why not? We should be eating them!”

Moore doesn’t need his “Trust Me” directives anymore, and that’s not just due to the slew of awards he’s won: “I got my soldiers out there preaching the gospel—my customers are telling folks, ‘Yeah, go to Saltbox and try this!’” says Moore.

It’s always been about more than just logistics—there’s an educational component to learning about local seafood that the lack of crucial infrastructure has only made more pressing. In the case of North Carolina seafood, most of us didn’t even know all that we were missing out on.

“Growing up in eastern North Carolina, we ate a whole lot of whole fish, smaller fish like croaker and spot. Unless you’re regionally connected to it as a part of your heritage, you would never see those fish on the menu. And why not? We should be eating them!”

When I was growing up in the late 1980s and early ’90s in Apex, we got our shrimp from a man across the street from Holt & Sons Auto Repair who sold them, fresh from the coast, out of a cooler; in the fall and winter, the same spot was occupied by a different man selling chowchow from his pickup. If a special occasion merited shrimp, my mom knew where to go, just as she knew which farm stand to go to in the summer for fresh corn or squash.

The popularity and proliferation of farmers’ markets helps, but finding these spots can be a long, often communal process: it’s tips from old-timers, trips to local markets and restaurants, and drives spent scanning the streets, circling back to check out a hand-written sign or curious-looking Quonset hut.

Such stomach-led learning takes time—it’s something that gets shared through interpersonal connections, like generous friends or skilled guides like Moore, who brings it to the table with enthusiasm, knowledge, and trust. There’s a reason we don’t tell people we don’t like where our favorite restaurants are—not only do we not want to run into them, but we don’t want to mar the experience of something special with someone who isn’t.

Locals Seafood’s expansion will allow outstanding chefs like Moore and Reusing to get the raw materials they need to fuel their creative visions, explore culinary traditions, and preserve cultural heritage.

It will also help ordinary folks like me learn to cook a fish I’ve never seen before, even though it may have swum past me in a nearby body of water. A patient fishmonger at Locals’ counter can explain what it is and detail how to prepare it. Or maybe I’ll learn to shuck an oyster or clean a soft-shell crab in one of the market’s demo classes. Whatever the case, the story of the species will start to be told, just in finding out where it’s from and how to eat it.

“What we really care about is our roots of just getting fish from point A to point B,” Peterson says. “When you come to us to buy your seafood, you’re seeing what’s actually happening on our coast. We won’t have mahi but a couple weeks a year, because that’s when they’re catching mahi off the coast.”

Zack Gragg portions blueline tilefish at the Locals Seafood market. Photo by Angelica Edwards.

“But we have lots of other fish,” he continues, “and we can tell those stories—introduce people to something like amberjack or tilefish, black drum, red drum—all these species off our coast that come and go in season. That’s what we’ve been doing for over 14 years at farmers markets—telling that story and letting folks know, ‘Hey, this is something good to try off our coast and it’s a great resource.’”

The expansion also allows the business to tell these fish and shellfish stories to more people in farther reaches of the state, making North Carolina seafood more accessible.

Such infrastructure only becomes more important as the word travels regarding the value of what chefs like Moore and Reusing have long held as a cherished resource. In other words, once you learn the story of a fish—a sheepshead, say—and get a taste for it, you might be willing to pay more for it next time.

“It’s kind of ironic that in making underutilized fish more expensive, it might actually protect the fisheries in the future,” Reusing says. “When the community starts to see ‘Oh, there’s value in this,’ it becomes something that is worth taking care of.”

“I’ve always been a big proponent of this idea that if we live by a body of water—which we do—that has a beautiful, bountiful amount of local species, we should be eating them,” Moore says. “Locals was—and still is—a wonderful partner in making sure we push this idea of ‘North Carolina first’ in terms of seafood and co-brand North Carolina as not just barbecue but for seafood.

Comment on this story at food@indyweek.com.